A village murder, a trusted voice, and a reader quietly led astray. A century after it was published, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd still dazzles. Not just for its audacity, but for the deep, almost mischievous pleasure of watching Agatha Christie turn the act of reading itself into the ultimate puzzle.

Why Christie’s Most Audacious Novel Still Astonishes

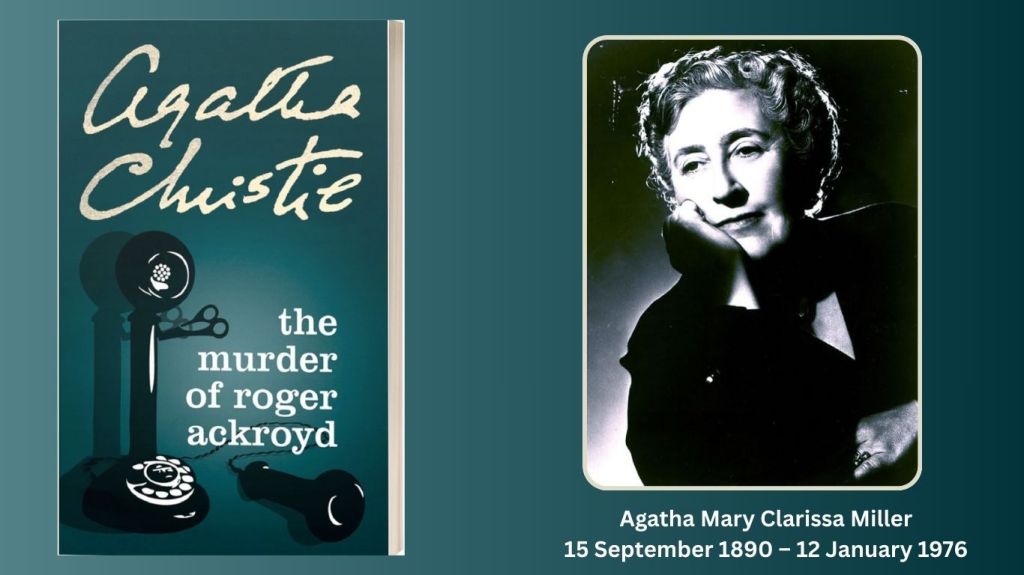

Few works in detective fiction provoke as much admiration, debate, and sheer delight as Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926). A century after publication, it continues to be read, taught, dissected, and imitated, its final revelation still capable of startling first-time readers and impressing seasoned ones. The pleasure of reading Roger Ackroyd springs not simply from its famous twist, but from the way Christie achieves that twist: through impeccable narrative engineering, psychological insight, social observation, and an almost invisible artistry that hides its brilliance in plain sight.

More than a game with the reader, it is a novel about the act of reading itself: about attention, trust, and the power of perspective. And within Christie’s own canon, it stands as a watershed: the moment she expanded the possibilities of the traditional whodunit while reaffirming her mastery over its rules.

The Pleasures of Christie’s Storytelling: Familiarity and Subversion

Part of the allure of reading Christie is the familiar texture of her fictional worlds. Roger Ackroyd begins like many Golden Age mysteries: a quiet English village, a shocking death, a cast of suspects with secrets, and Hercule Poirot appearing, retired, in the most unlikely place. King’s Abbot, with its gossip networks and genteel rhythms, offers readers the cosy comfort that Christie so often perfected.

Yet this comfort is the Trojan horse. Christie uses the serene village atmosphere to lull the reader into a sense of security. The narrative voice, the affable Dr James Sheppard, seems perfectly conventional, a village doctor in the mould of Dr Watson. The early chapters lean into the familiar pleasures of routine: breakfast conversations, odd neighbours, the daily rounds. The impression is one of predictability, which Christie uses as a form of misdirection. What seems ordinary becomes the mechanism for the extraordinary.

Reading Roger Ackroyd is pleasurable because it offers the satisfaction of pattern recognition, of thinking, ‘I know how a Christie mystery works’, while simultaneously preparing to dismantle that assumption. The most delightful part is not merely being fooled, but realizing afterward how meticulously Christie laid the groundwork for the deception.

Narrative Deception: The Radical Use of the Unreliable Narrator

The feature that most distinguishes Roger Ackroyd from the general run of murder mysteries is, of course, its ground-breaking use of an unreliable narrator. While detective fiction had occasionally flirted with unreliable accounts earlier, no one had used the device so boldly and so fairly. Christie obeys the genre’s central principle, ‘the reader must have the same information as the detective’, even while exploiting the limitations of point of view.

Dr Sheppard records only what he wishes to, filters events with strategic vagueness, and arranges his narrative with the consciousness of someone who knows he is writing a document that may be read as evidence. His omissions become revelations in retrospect. The greatest pleasure in rereading the novel lies not in discovering who the murderer is, but in marvelling at how Christie uses language to obscure without lying. Every piece of misdirection is technically honest. Sheppard says everything and nothing at once.

For example, his description of the crucial moment involving the locked study and Ackroyd’s body contains no untruth; it is the reader who fills in the gaps with assumptions. Christie’s brilliance is that she anticipates those assumptions and turns them into the foundation of her twist. This manipulation of narrative perspective not only subverts convention; it deepens the psychological dimension of the story. Sheppard is not a cardboard villain but a complex presence: insecure, resentful, observant, and profoundly chilling in his emotional detachment. His voice, calm and controlled, is the perfect camouflage for a murderer.

A Puzzle Novel That Is Also a Study in Human Nature

Christie often claimed she wrote puzzles, not psychological novels, but Roger Ackroyd is among her most psychologically acute works. Where many Golden Age mysteries rely on external clues – footprints, time-tables, missing weapons – this one hinges on the inner life of its narrator. Hercule Poirot’s method in this novel is explicitly psychological rather than forensic: ‘It is the psychology I seek, always the psychology.’

Much of the pleasure of the novel comes from the interplay of norms and aberrations within King’s Abbot society. Christie constructs a village that runs on gossip, small jealousies, financial anxieties, and social competition. These everyday human tensions form the backdrop against which murder becomes both shocking and disturbingly plausible. Characters like Caroline Sheppard, Dr Sheppard’s sister, add to the richness of this world. She is a precursor to Miss Marple: sharp, intuitive, socially perceptive, and a delightful commentary on the detective figure. Caroline represents the village as collective detective: nosy yet often accurate, guided by instinct where Poirot uses method.

Christie also probes the nature of secrecy: its power, its fragility, its ability to warp relationships. Almost every character harbours a secret unrelated to the murder, and the pleasure of the novel lies in watching Poirot patiently uncover these tangles. The layers of concealment – financial trouble, love affairs, blackmail – create a narrative density that enhances the final reveal by showing how murder grows out of a web of ordinary human frailties.

Fair Play and Reader Engagement

What makes Roger Ackroyd so satisfying, even after multiple readings, is that Christie plays absolutely fair. Every clue, every motive, every piece of misdirection is visible. The twist does not arise from withheld information but from withheld interpretation. Christie trusts the reader’s intelligence, and counts on their biases.

This ‘fair but ruthless’ approach is what separates the novel from ordinary whodunits. Many mysteries rely on obscure clues or last-minute revelations. Christie instead uses structure (Sheppard’s narrative mirrors his psychology); ellipsis (what is not said becomes as important as what is said); assumption (she anticipates the reader’s tendency to trust the narrator); pattern disruption (using the Watson-like figure as the murderer violates a genre convention without breaking it).

The reading pleasure comes from hindsight clarity. Once the solution is known, every earlier chapter seems illuminated from a new angle. The novel rewards rereading more than almost any other Christie work. The reader becomes a detective of the text itself.

Its Place in the Christie Canon: A Bold Experiment That Became a Landmark

Within Christie’s vast oeuvre, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd occupies a unique and exalted position. It is her first mature masterpiece, the novel that made her famous, and the book that established her as the reigning queen of the genre. Although The Mysterious Affair at Styles introduced Hercule Poirot and The Murder on the Links refined her technique, Ackroyd was the novel in which Christie fully embraced narrative innovation.

Its significance within the canon can be measured on several levels:

A Turning Point in the Poirot Character

Poirot in this novel is more reflective, more patient, and more human. His interactions with the villagers show a warmth and humour that contrast with the more formal Poirot of later decades.

A Template for Christie’s Later Experimentation

Many of Christie’s later masterpieces – And Then There Were None, The ABC Murders, Endless Night, Curtain – play with structure and perspective in daring ways. Ackroyd is the prototype for this experimental strand within her oeuvre.

A Canonical Moment in Golden Age Detection

The novel is often cited alongside Dorothy L. Sayers’ The Nine Tailors and Anthony Berkeley’s Poisoned Chocolates Case as defining the possibilities of the genre. Its twist has entered cultural memory.

A Book That Cemented Her Global Popularity

After Ackroyd, Christie was no longer simply a novelist. She was a phenomenon. The controversy around the twist, including negative reactions from purists like S. S. Van Dine and Raymond Chandler, only increased its fame.

The Ethics of Deception: Why Readers Don’t Feel Cheated

One of the enduring questions about Roger Ackroyd is why readers rarely feel angry at the twist, despite being deliberately deceived. The answer lies in Christie’s impeccable execution. She involves the reader as a collaborator in the deception: they mislead themselves through assumptions about narrative convention. Christie exposes the mechanics of reading as much as the mechanics of crime.

Moreover, the twist brings with it an almost cathartic pleasure: the joy of being outwitted by a master. Christie’s deception is elegant rather than manipulative. And in Poirot’s final confrontation with Dr Sheppard, there is a moral symmetry that satisfies the reader’s sense of justice.

Why The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Still Matters

Reading The Murder of Roger Ackroyd today is to rediscover why Agatha Christie endures. It is not merely the shock ending, but the craftsmanship that leads to it: the carefully built village world, the subtle psychology, the precision of language, the rhythmic unfolding of clues. Christie respects her reader enough to challenge them, while never compromising on clarity or pace.

In the Christie canon, it represents a daring leap, one that changed the rules of the detective story while honouring its traditions. Its place in the history of crime fiction is assured because its pleasures are timeless: intellectual stimulation, emotional engagement, narrative surprise, and the irresistible charm of Hercule Poirot at his finest.

Above all, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd exemplifies the joy of reading itself. It is a reminder that stories can entertain while provoking thought, and that even within a highly structured genre, there is room for profound creativity. It remains, unmistakably, one of the greatest murder mysteries ever written. Not merely because of how it ends, but because of how it invites us to read.

Leave a comment