A year of paradoxes, where record-breaking box-office triumphs coexisted with a persistent creative unease. While familiar formulas dominated the multiplexes, Bengali cinema’s most rewarding achievements lay elsewhere: in intimate, risk-taking films marked by aesthetic rigour, emotional intelligence and quiet daring. Here is a personal selection of 2025’s finest.

It has, by any measure, been a remarkable year for Bengali cinema, buoyed by a string of box-office successes the industry has proudly celebrated. For a sector more accustomed to brickbats than bouquets – criticised for its supposed lack of vitality, its reliance on tired genres, and its hesitance to experiment – these wins have been heartening. As the year draws to a close, here’s a round-up of the best of Bengali cinema.

The box-office successes have been staggering, with Dhumketu, Raghu Dakat, Eken: Benaras e Bibhishikha, Amar Boss and Raktabeej 2 leading the way, earning revenues that, in the context of the Bengali film industry, are nothing short of mind-boggling. Srijit Mukherji, meanwhile, registered two sharply divergent triumphs in Shotyi Bole Shotyi Kichhu Nei (which earns a place on my best-of-the-year list) and Killbill Society (which does not). Yet these successes have not silenced the sceptics, and perhaps rightly so. With the exception of Shotyi Bole, which performed well despite the narrative risks it took, none of these blockbusters offered anything particularly new in terms of storytelling ambition or imaginative daring.

Much like last year’s Khadan and Shontan, they chose the safety of familiar terrain over the risks of cinematic innovation. Particularly disappointing were Amar Boss (Raakhee deserved a far better comeback to Bengali cinema), Grihapravesh (an overwrought homage to Rituparno Ghosh), Binodini and Devi Chowdhurani – the former a historical biopic of a remarkable woman, the latter an adaptation of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s novel – both undermined by juvenile execution and a lack of vision. There was also no escaping the spate of Ray-referenced films such as Joto Kando Kolkatatei and Sonar Kellay Joawkher Dhan; even the Eken film leaned heavily on homage, echoing Joi Baba Felunath, gestures that ultimately did little to honour the master’s legacy.

It is for these reasons that my list excludes these commercial juggernauts in favour of smaller, more intimate films – works that placed their faith in aesthetics, restraint and emotional intelligence rather than the comfort of repetition and nostalgia.

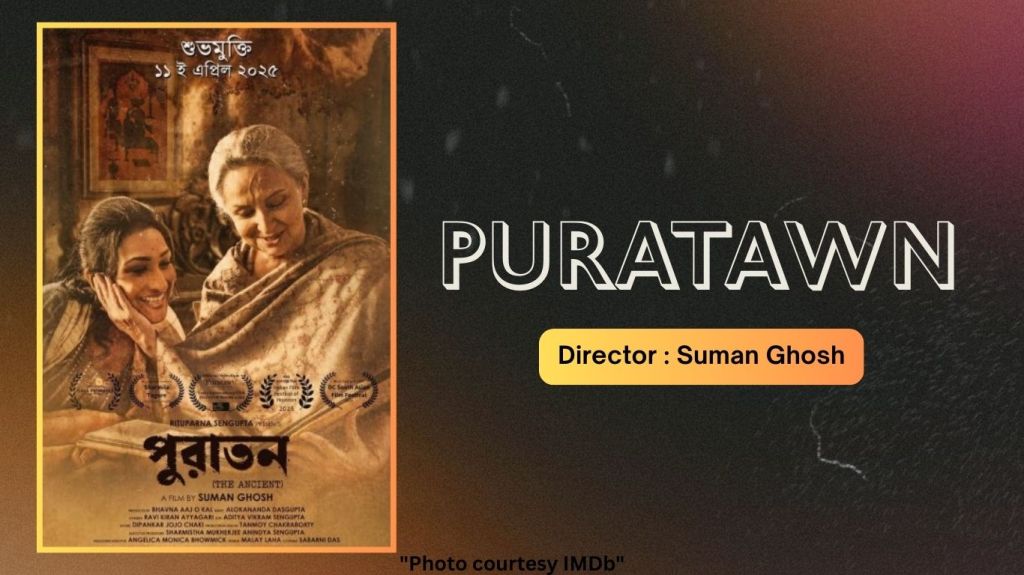

Puratawn (D: Suman Ghosh)

Puratawn marks a deeply moving return to Bengali cinema for Sharmila Tagore, and Suman Ghosh’s finest film yet. A meditation on memory, time and fading selves, it builds to an extraordinary six-minute silent sequence in which Tagore’s Mrs Sen wanders through objects from her past, an achingly tender interplay of performance and Alokananda Dasgupta’s exquisite score. Ghosh’s restraint, his feel for ageing and remembrance, and Ravi Kiran Ayyagari’s evocative visuals create a world where houses, trees and caves hold the imprint of lives lived. With superb support from Rituparna Sengupta, Indraneil Sengupta and Brishti Roy, Puratawn lingers long after its final frame. Suman also had a theatrical release for his insightful documentary, Parama: A Journey with Aparna Sen, and a book emerging from his conversations with the legendary director and actor, rounding off a very successful year for Suman.

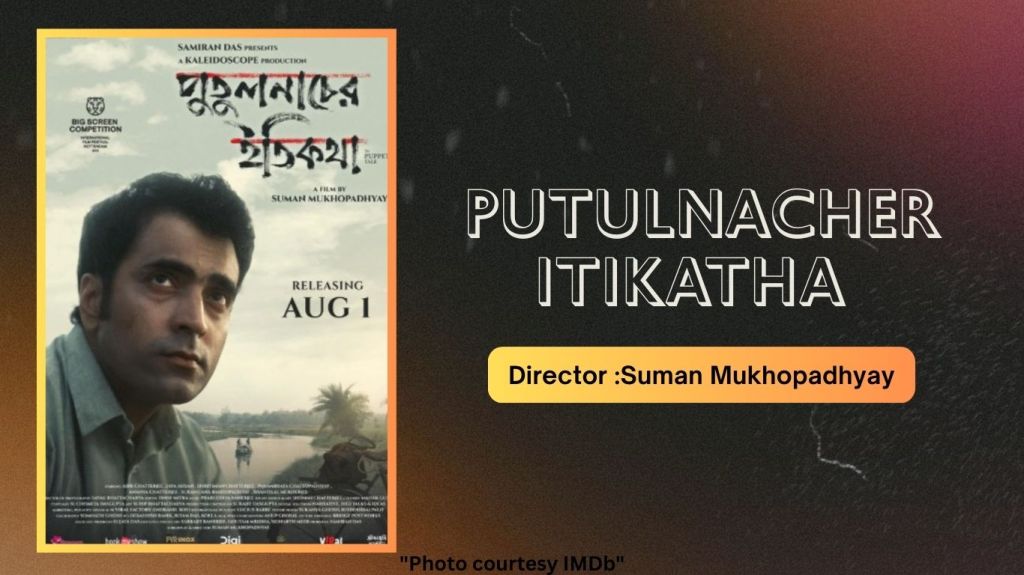

Putulnacher Itikatha (D: Suman Mukhopadhyay)

Putulnacher Itikatha, my co-candidate for the year’s best Bengali film along with Puratawn, is one of the year’s most quietly devastating films. Suman Mukhopadhyay adapts Manik Bandopadhyay’s classic with rare fidelity and imagination, shifting the story to the early 1940s and infusing its village world with the shadows of war, famine and moral decay. Abir Chatterjee delivers a career-best turn as a man torn between reason and inertia, while Jaya Ahsan’s luminous presence becomes the film’s aching centre. Rich in texture and atmosphere, the film probes desire, superstition and social hierarchy without nostalgia or simplification. A patient, unsettling, deeply resonant work that feels startlingly contemporary.

Shotyi Bole Shotyi Kichhu Nei (D: Srijit Mukherji)

Shotyi Bole Shotyi Kichhu Nei is one of the year’s most dazzling surprises. Srijit Mukherji takes the classic 12 Angry Men template and reinvents it with wit, ambition and enormous craft. Dispensing with the one-room claustrophobia, he sets the ‘jury’ across beaches, forests and flyovers, each location mirroring the characters’ biases and inner tumult. He adds women to the mix, opens up the crime’s world, and devises an ingenious narrative device to solve the absence of India’s jury system. Powered by superb performances and striking craft, the film becomes a sharp indictment of contemporary prejudices, proof that the original’s core remains timeless. The film compensated for the heavy-handed Killbill Society that went on to become one of the year’s big hits, but left me cold.

Mayanagar: Once Upon a Time in Calcutta (D: Aditya Vikram Sengupta)

Sengupta’s Mayanagar unfolds like a living, breathing portrait of Calcutta in ceaseless flux. The film traces the city’s shifting rhythms through characters caught between memory, loss and the lure of reinvention. Striking, surreal imagery meets a sharply etched narrative as Sengupta renders the metropolis not as backdrop but as a sentient organism shaping every life it touches. Sreelekha Mitra and Bratya Basu anchor this tapestry of longing, decay and stubborn hope. Accessible yet deeply layered, Mayanagar emerges as one of the year’s finest, an unsentimental, haunting ode to a city forever becoming.

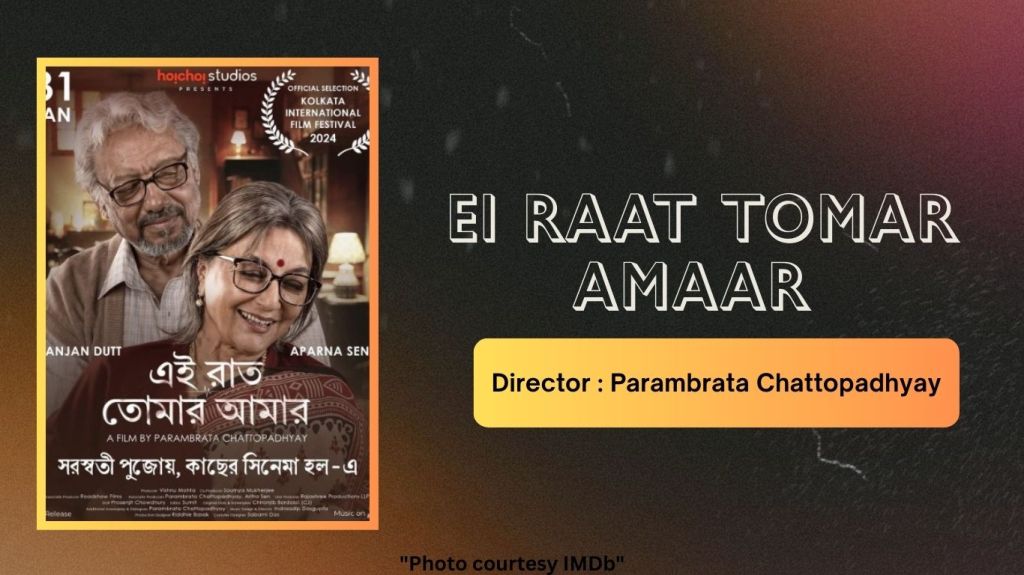

Ei Raat Tomar Amaar (D: Parambrata Chattopadhyay)

Parambrata Chatterjee’s Ei Raat Tomar Amaar was never built for the box office, but it stands out as one of the year’s most quietly remarkable Bengali films. Driven by a beautifully crafted script and Parambrata’s unfailingly honest direction, the film nurtures the rare courage to place Aparna Sen and Anjan Dutt, both in their seventies, at its centre, trusting their craft and lived depth. What emerges is an elegant, restrained portrait of ageing, companionship and dignity, elevated by precise writing, luminous performances and meticulous craft. It’s a reminder that Bengali cinema thrives when artistic integrity and thoughtful production walk hand in hand.

Honourable Mentions

Arjun Dutta’s Deep Fridge, this year’s National Award winner for Best Bengali Film, is a quietly devastating study of love, guilt and the emotional cold storage we retreat into. Centred on a storm-hit reunion between ex-spouses played by Abir Chatterjee and Tnusree Chakraborty, the film unfolds with exquisite restraint. Abir’s brilliantly internal performance anchors a narrative of frozen feelings slowly thawing, while Dutta’s craft – precise sound, unfussy camerawork, unforced emotion – keeps the drama intimate and believable. Despite minor excesses in dialogue, Deep Fridge stands out for its maturity and emotional clarity: a beautifully calibrated portrait of heartbreak, reckoning and release.

Dear Maa is a quietly affecting thriller that uses its mystery framework to explore parenthood, emotional inheritance, and the making, not merely the naming, of a mother. Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury revisits familiar themes of love, regret and relational fragility, but with a gentler, more searching gaze. Despite occasional overstatement, the film’s emotional intelligence, elegant structure, and sensitive music design make it a layered, lingering portrait of motherhood as choice, effort and evolving selfhood.

Leave a comment