I have been drawn to Larry Darrell’s quiet, impossible freedom for decades. I revisit Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge to understand why Larry’s detachment still steadies me and unsettles me at the same time, and why his path continues to beckon.

Larry Darrell: An Impossible Ideal

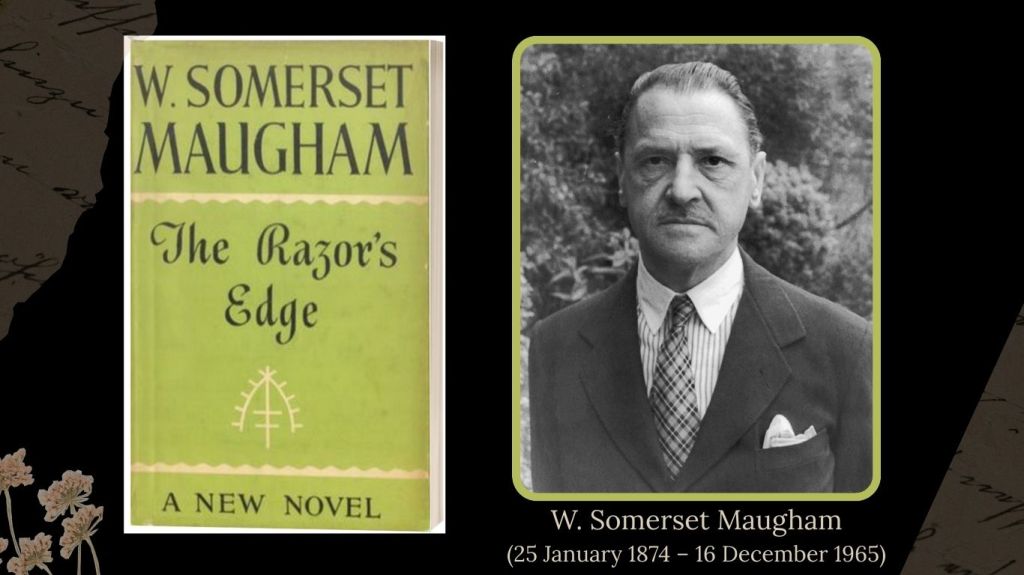

There are books that remain with us as moral signposts, their characters breathing into our own consciousness long after we have turned the last page. Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge is one such work that has, over the years, acquired the quality of a quiet companion, its pages echoing the questions that define the human condition. And at its centre stands Larry Darrell, one of literature’s most elusive, haunting figures, a man who refuses the world and, in doing so, attains a freedom that most of us can only envy from a distance.

Maugham’s genius lies in his ability to turn the search for meaning, a theme so often inflated into mysticism or abstraction, into the most intimate of human journeys. The Razor’s Edge opens in the aftermath of the First World War, when the certainties of the old world have collapsed. Larry Darrell returns from the war changed, carrying within him an unhealed wound, one that is not physical but existential. He has seen death close enough to realize how transient everything is – wealth, ambition, even love. The war, Maugham tells us, ‘had left him with a hunger of the soul’.

For most of us, that hunger would be inconvenient. We would bury it beneath work, relationships, or the relentless pursuit of comfort. But Larry, with a stillness that borders on the sublime, refuses to bury it. He walks away from a secure future, from Isabel’s love, from the American dream. In that gesture, I find something deeply stirring. It is not merely rebellion or idealism; it is a quiet act of truth-telling. He knows, instinctively, that the life offered to him by society is not his own, that its promises of success and happiness are traps disguised as blessings. He refuses to live by borrowed meaning.

What has always drawn me to Larry is not just his quest for enlightenment, but the manner in which he undertakes it, without noise, without sermon, without the self-righteous glow of a convert. In Paris, he reads philosophy, works menial jobs, lives simply, and thinks deeply. There is an exquisite ordinariness to his search: he is not the ascetic on a mountaintop, nor the prophet in the desert. He is a man living among others, but detached, like a mirror reflecting the world without being coloured by it. When he goes to India, it is not as a pilgrim in search of spectacle, but as a seeker who wishes to ‘learn to be at peace’.

That phrase ‘learn to be at peace’ has stayed with me through years of inner restlessness. In a world obsessed with achievement, Larry’s withdrawal feels almost scandalous. His refusal to participate in the game of acquisition, his serenity in the face of material temptation, his ability to lose everything and still feel enriched – all of it forms a kind of moral compass for those of us who struggle to live without clutching. When Isabel, unable to understand him, asks whether he ever thinks of her, his answer is disarming: ‘I can’t help thinking of you sometimes, but I’m not unhappy about it. It doesn’t hurt me. You’re a memory, that’s all. A pleasant one, but a memory.’ How many of us can say that – to hold love, loss, and solitude in the same breath without bitterness?

Maugham structures the novel as a series of encounters, seen through his own eyes as narrator. He is the observer, the chronicler of Larry’s choices, and through his bourgeois sensibility we glimpse the magnitude of Larry’s divergence. The other characters – Isabel, Gray, Elliott Templeton – embody the materialist world in its varied forms: ambition, comfort, vanity. Against them, Larry appears almost spectral, a figure moving to an inner rhythm they cannot hear. Yet Maugham never romanticizes him. There is always a trace of doubt: is Larry naïve, or truly wise? Is he wasting his life, or discovering its essence? It is precisely this ambiguity that gives Larry his power. He is neither saint nor fool; he is both.

The First Experience of The Razor’s Edge

When I first read The Razor’s Edge in my early twenties, I was struck by the audacity of Larry’s freedom. I was at a crossroads in my life. I held and resigned from multiple jobs in accounts and finance and hated every day of it. I even went in search of a spiritual guru, and found one in a woman in Barasat who had a small ashram. That led to its own sorry saga for over thirty years. Yet, so ingrained were the themes of settling down, holding on to a job, playing by the rules society dictated, I just couldn’t break out like Larry did. My guru could not give me the strength that Larry’s encounter with the guru gave him. I was tangled in the webs of expectation, the need to succeed, to belong, to be seen. Larry’s rejection of all that felt like a breeze from another world. I envied him and rationalized: the character is fictional, and one can do almost anything in fiction.

It was only later, when life’s complications deepened, that I began to understand the quiet heroism of his detachment. There is something profoundly modern about his quest – a man seeking spiritual meaning in a disenchanted world. In the decades since the book was written, the hunger Maugham describes has only intensified. We have built higher towers, faster machines, and yet, as Larry foresaw, the soul remains famished.

Maugham’s prose is deceptively simple. He writes with a clarity that borders on the surgical, yet within that simplicity lies immense depth. The title itself, drawn from the Katha Upanishad, captures the essence of Larry’s journey: ‘The sharp edge of a razor is difficult to pass over; thus the wise say the path to salvation is hard.’ It is no coincidence that Maugham found his central metaphor in Indian philosophy. The novel’s spiritual core lies in that idea of walking the narrow path between indulgence and renunciation, between engagement and withdrawal. Larry embodies that razor’s edge. He lives in the world but is not of it.

When he returns to America after years of wandering, Larry is transformed. He has worked in ashrams, read scriptures, meditated in caves, and yet what he brings back is not doctrine but stillness. He seeks nothing; not even to convert others. Maugham’s narrator calls him ‘a soul that has found what it sought’. For me, that is the ultimate freedom: to live without grasping. When Larry says he wishes to drive a truck or work with his hands, it is not out of ascetic denial but from a genuine sense of equality between all forms of work. He has dismantled the hierarchy of human pursuits. He has nothing, and yet he is rich.

Perhaps what moves me most about Larry is his gentleness. There is no anger in his renunciation. He does not condemn Isabel for her choices, nor mock Elliott’s vanity. He understands that each person must live according to his nature. His compassion is rooted in clarity. And so, when he says that he wishes only ‘to live a little quietly, to do a little good’, it feels less like modesty and more like revelation. In those few words lies the essence of his philosophy: a life pared down to kindness and calm.

A Moral Hero

To call Larry a hero feels almost wrong, for he would have rejected the term. But he is, for me, a moral hero, the rare individual who has seen through the illusion of possession. In an age where identity is constructed through consumption, Larry reminds me that freedom begins with letting go. His journey teaches that one need not renounce the world to be detached from it; that solitude can coexist with affection; that simplicity is not poverty but plenitude.

Each time I return to The Razor’s Edge, I find in Larry a mirror for my own restlessness. He is the voice that whispers when life grows too noisy: ‘You don’t have to chase. You can simply be.’ There is immense courage in that simplicity. It is easier to conquer mountains than to conquer desire. Larry’s achievement is inward, invisible, and therefore eternal.

Maugham ends the novel with characteristic irony, noting that everyone except Larry gets what they want: Isabel her comfort, Gray his wealth, Elliott his social triumphs. And yet, he adds, ‘They are all perfectly satisfied. But perhaps if you look closer, you will see that they are not quite happy.’ Larry, alone among them, walks away, unattached, serene, unburdened. He has found peace not by fleeing life but by ceasing to demand anything of it.

That, to me, is the ultimate victory. To live in a world that insists on defining you and yet remain undefined, to walk lightly through it, like a breeze that touches everything and clings to nothing. That is the razor’s edge. Larry Darrell lives there, balanced between the visible and the invisible, and invites us to join him.

And though I cannot walk as lightly as he does, I find comfort in his example. A reminder that freedom is not a place one reaches, but a way of being. Of late, particularly over the last couple of years, and the almost traumatic past few months, as I have often been overwhelmed by circumstances and my weaknesses, every time I feel ensnared by the noise of ambition or the ache of attachment, I think of Larry – his quiet smile, his calm acceptance – and for a fleeting moment, I, too, feel free.

Leave a comment