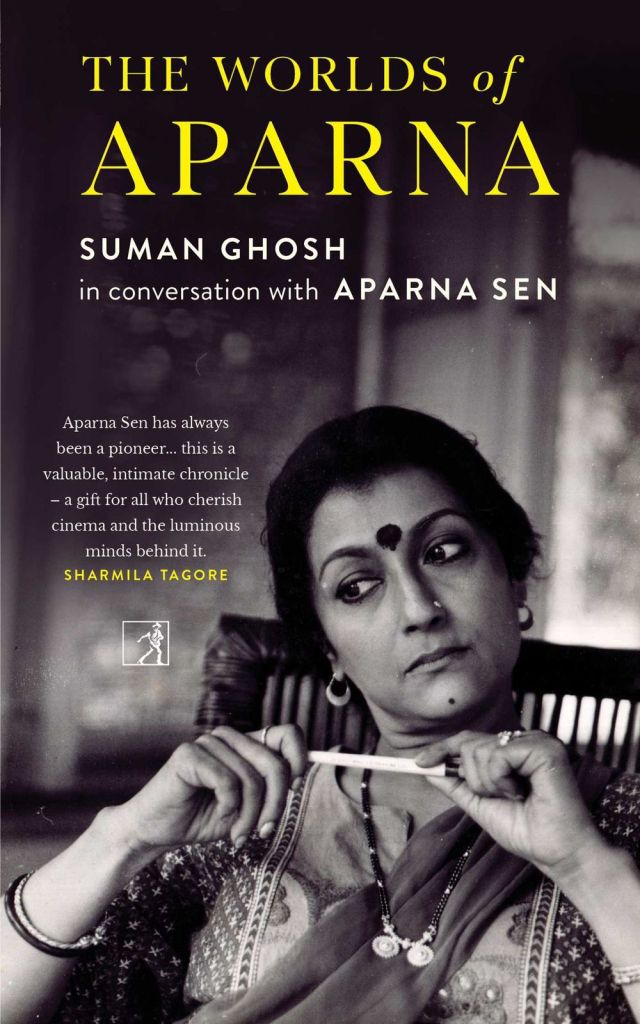

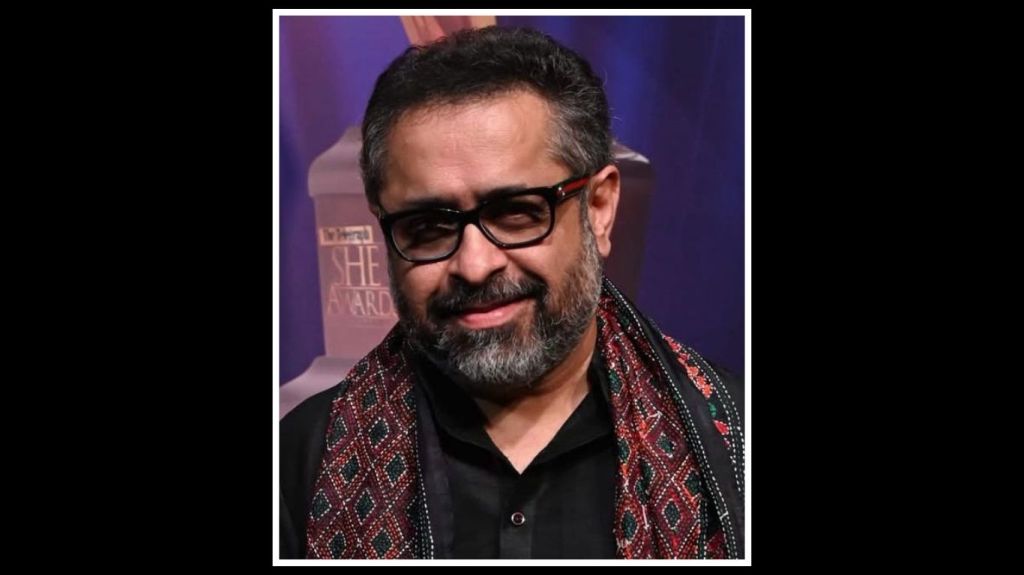

Few figures in Indian cinema command the kind of reverence and affection that Aparna Sen does – actor, director, writer, editor, and an unwaveringly independent voice for over six decades. As she turns eighty, film-maker and academic Suman Ghosh offers a deeply personal tribute in The Worlds of Aparna, a book born of years of conversation and friendship. Structured as an intimate dialogue between two artists, the book moves beyond filmography to reveal the person behind the icon: curious, fearless, humane and profoundly honest. In this interview, Suman Ghosh reflects on the making of the book, his long association with Sen, and the many ‘worlds’ that define one of Indian cinema’s most distinctive creative minds.

‘Being in the academic profession – I’m a professor myself – it is standard protocol that when a senior academic turns 70, 75, or 80, a conference is held in their honour. Students pay tribute by presenting papers and organizing the event. That is the tradition in academia. Of course, in the world of cinema, there is no such formal custom. In that academic spirit, I would say that this book is my homage to her, a student paying tribute to a professor. And I believe I speak not just for myself but for countless other film-makers who have been inspired by her work. So, this book stands as an homage to her on her eightieth birthday.’ – Suman Ghosh

The Worlds of Aparna draws from extensive conversations with Aparna Sen. What was the process of earning her trust and creating an atmosphere where such candid, introspective dialogue could unfold?

I first met Aparna Sen while shooting Kadambari, in which her daughter Konkona was playing the lead. Aparna had come to the set, and of course, she has always been such an icon that I was far too much in awe of her to even have a proper conversation. I was simply overwhelmed by her presence.

Later, when we worked together on Basu Paribar, our interaction began in a formal actor–director capacity. I remember during one of our addas on that shoot, she said to me, ‘You often go to Soumitra Chatterjee’s place for addas, don’t you? Why don’t you come and visit me too? We can have a chat.’

I laughed and told her, ‘How can I just call Aparna Sen and say I’m coming over for an adda?’ And she said, ‘Dekhoi na kore!’ (‘Why don’t you try and see!’)

So I actually did go, and we ended up having a wonderful session together. That’s really how our friendship began, around 2017 or 2018, during the Basu Paribar days … and it’s continued ever since, without pause. By the time I began writing this book, we had already spent several hours together in conversation, and I think a deep bond had formed between us by then.

Having known Aparna Sen both as a film-maker and as a public figure, how did your perception of her evolve through these interviews? Did anything surprise you about her creative or personal worldview?

No, you see, when I decided to make the documentary on her, and later, the book, I already had a deep understanding of who she was, after spending so many hours with her. I felt it was imperative to let the larger world know not just about her as a celebrated film-maker, actor, and political figure, or as a voice for feminism and many other causes, but about the person behind all that. So, to answer your question, nothing particularly surprised me. I already knew what I wanted to convey and preserve for posterity – the essence of her persona – which I believe is especially important in these strange and uncertain times we live in.

The book’s title suggests multiplicity. What are the different ‘worlds’ you discovered in her – as an actor, director, writer, and thinker?

So, The World of Aparna is, in a sense, a take on The World of Apu …you know, part of Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy … the many worlds of Apu.

Aparna Sen, of course, is known to us primarily as a film-maker and actor. But for those who grew up in the 1980s and ’90s, she was also the editor of Sananda, that immensely influential women’s magazine which, I would say, helped advance the cause of feminism and shook the Bengali socio-political milieu.

Her political voice, too, has always been distinctive. And I somehow felt that all her different avatars – whether as film-maker, actor, editor, or political thinker – were bound by a single purpose. Through them, she sought to communicate something essential to the larger world, whether it was about feminism, politics, or cultural identity.

What I wanted to capture in this book was that underlying persona, the same essence manifesting through various roles, each a different garb but driven by one spirit. It may appear to be a multiplicity, but at its core, it is the same self, expressing itself through different forms. That is what I wanted to convey in The Worlds of Aparna.

Aparna Sen has often been described as someone who bridges the personal and the political in her cinema. How consciously does she view her work in that light, based on your conversations?

I think in the book I have tried to bring that out … that idea of what defines a true artist. When we think of the artists we’ve grown up admiring – Rabindranath Tagore, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, or, on the international front, Eisenstein and Bertolt Brecht, among others – one thing becomes clear: in a true artist, the personal and the political coalesce in remarkable ways. That, I believe, is what an artist should be: a voice that serves as the conscience of society.

I don’t think she consciously approaches her work with that awareness, and that’s precisely what I like about her. She is honest about who she is, and that honesty finds its way into her work naturally, almost effortlessly. If it were deliberate, it might have felt forced. But the fact that it isn’t – that she isn’t self-conscious about it – is, I think, part of what draws me to her.

Many of her films – 36 Chowringhee Lane, Paroma, Mr. and Mrs. Iyer, The Japanese Wife – centre on women negotiating inner freedom. How does she articulate her feminist vision, and has it changed over the decades?

I don’t know whether her vision has changed over the decades, because I didn’t know her in the ’80s, ’90s, or even the first decade of the new millennium. But what I can say is that there’s a very interesting discussion on feminism in the book. What struck me most was her viewpoint that she is, first and foremost, a humanist.

Issues such as child trafficking or labour exploitation disturb her just as deeply. Yet, she views the world through a woman’s eyes, and that gaze is vital. It shapes how she engages with the world, and it manifests naturally in her cinema, in her writings, and even in her work as editor of Sananda. That, I think, is the essence of her feminist vision.

But again, as I mentioned earlier, she doesn’t consciously try to propagate a cause. It’s simply who she is, and it flows organically into everything she creates. Her feminist vision, as you rightly pointed out, is unmistakable, powerfully expressed in the films you mention. These works have been seminal in shaping the way feminism has evolved in our country.

Was there a particular conversation or anecdote during the interviews that revealed something quintessential about her, something that stayed with you long after?

Yes. I remember asking her, in the current socio-political climate of the country, whether she was ever afraid to speak out. Everyone knows that she has always been outspoken, regardless of which political party is in power. And she said – this is in the book too, as part of a larger discussion on the subject – ‘Aar ei boishae aamae ki korbe? Mere phelbe?’ (‘At this age, what can they do to me? Kill me?’).

It was the way she said it … so calm, so utterly nonchalant … that struck me. She is prepared to face the ultimate consequence, yet that will never stop her from speaking her mind. I think that kind of courage is a rarity today. That moment stayed with me long after the interview.

Aparna Sen’s cinema is deeply rooted in Bengal yet speaks to universal human experiences. How does she herself navigate that balance between the local and the global?

Well, if you read the book, you’ll see that it explores in detail how she grew up, her foundations, what shaped Aparna Sen, her vision, and her philosophy of ideas. You get a vivid sense of her multicultural upbringing: her parents, the milieu she was part of, and the remarkable artists – Satyajit Ray, Bishnu De, Paritosh Sen, among others – who would often visit their home. The way she was raised gave her a distinctly international and cosmopolitan outlook. And, as the saying goes, the best way to be global is to be local. Aparna embodies that: deeply rooted yet expansively global. As I often say, there are two avatars of Aparna Sen for me: one is Rina-di, and the other is Aparna Sen.

I have seen her in many moods. For example, when I visit her at home, she has this motherly warmth and care, like a quintessential Bengali mother, or perhaps an affectionate elder sister, or even a close friend, all marked by those deeply Bengali traits. And then, when you see a film like Paroma or Paromitar Ek Din, you witness how perfectly she embodies the essence of a North Calcutta woman. Yet, on the other hand, Aparna Sen is also an international figure, progressive, intellectually curious, and deeply aware of what’s happening in the world. This apparent dichotomy fascinates me, and I hope readers of the book will sense exactly what I mean by that.

As a film-maker yourself, how did engaging so closely with her process influence or challenge your own understanding of cinema?

There are extensive sections on her film-making process in the book. I don’t know if it necessarily challenged my own viewpoints, but it was certainly a profound learning experience, an exploration of her mind and creative method. We went through every aspect of film-making: working with actors, music, editing, production design, cinematography, how she interacts, the kind of briefs she gives, how she develops a concept, and so on. It was an immense learning experience for me. I can’t say how much it challenged me personally, but it remains an ongoing process of discovery. I’m sure it will be equally fascinating for many aspiring film-makers and even established ones to understand the mind behind such iconic films.

The book is as much about a dialogue between two creative minds as it is about Aparna Sen’s life. How did you decide the tone and structure of these conversations to retain their intimacy and spontaneity?

I would name three books that have been very influential to my thought process as a film-maker. The first is a wonderful book that records a conversation between Billy Wilder and Cameron Crowe, titled Conversations with Billy Wilder. It’s fascinating because Crowe, being a director himself, explores Wilder’s mind in a way that I think a journalist or writer might not have been able to fathom. And of course, there’s the iconic Hitchcock/Truffaut, another instance of one director interviewing another.

Lastly, I would mention the book by Shyam Benegal on Satyajit Ray. Benegal made a documentary on Satyajit Ray as well, and that long conversation with him was later published in book form. These three books have influenced me deeply, especially in terms of tone and structure. Although most of these works focus solely on the film-maker, in the case of Aparna Sen, she is much more than that. She’s also a renowned actor, embodying multiple creative personas. Given our close friendship of nearly a decade, I could explore subjects that others perhaps could not. Most importantly, she was comfortable enough with me to open up. In that sense, I would say I took advantage of that relationship, lovingly and respectfully, for the purpose of this book.

Finally, if you were to distil one defining quality of Aparna Sen – the thread that connects her life, art, and worldview – what would that be?

You have asked for one defining quality, can I take the liberty of mentioning two defining qualities? One is extreme honesty. You might not agree with what her viewpoints are. You might find her viewpoints objectionable when she talks about politics or her viewpoint in her films, but I can vouch for the honesty with which she approaches every aspect of her life. Of course I am no one to vouch about that, but again I am taking advantage of being extremely close to her personally.

You know, the extreme honesty of this lady stands out. Unfortunately, honesty is a trait that is gradually being lost. Given the circumstances, the state of the world, and the way we navigate life today, we tend to make compromises here and there. But she is exceptionally honest. And I cannot tell you how much that has influenced me. As I grow older as a film-maker, I tell everyone … my cast, my crew and even myself … just make an honest film. The film may be good, bad, or anything in between, but be honest. Interacting with Aparna Sen made me realize how deeply that honesty runs in her, both as a person and as an artist.

And another remarkable quality is her incredible, almost childlike curiosity about the world. She turns eighty on the 25th of October, but honestly, it could just as well be her eighth birthday … the same sense of wonder and enthusiasm remain. In the book, we talk about F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, and as you know from my work, Podokkhep was inspired by that story, where a man, as he grows older, gradually becomes more and more like a child.

Aparna Sen is like that, I think. As she grows older, what stands out is her childlike curiosity. She remains deeply inquisitive about so many things in the world, and it’s remarkable how she has preserved that quality even at the age of eighty.

Leave a comment