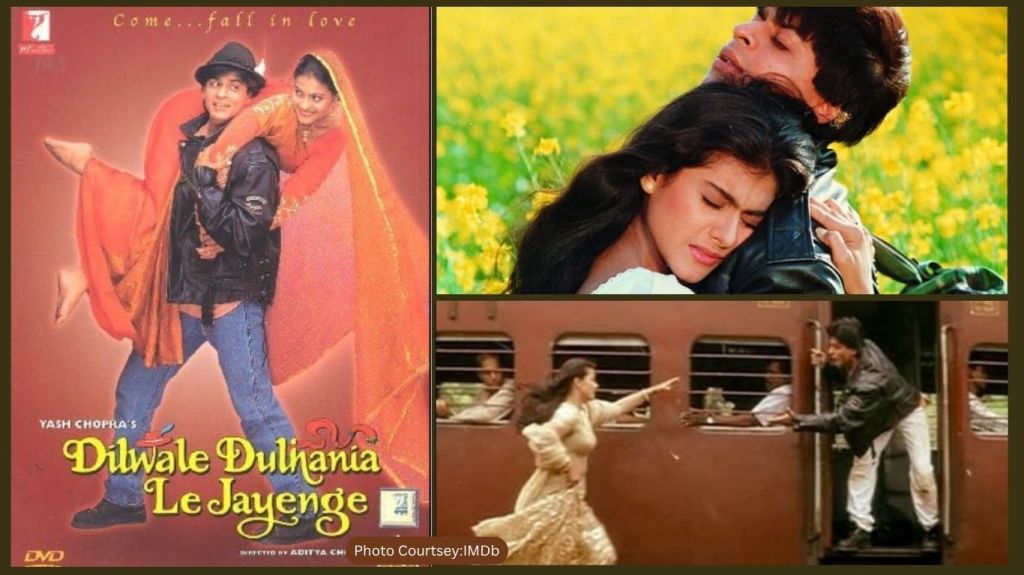

Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge turns thirty. For most of my generation, that sentence alone evokes a warm rush of nostalgia – mustard fields, big joint families celebrating the big fat Indian wedding, ‘Palat’. For me, it never did.

When I first saw Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, I felt left out of some grand collective swoon. Everyone I knew adored it. The charm, the music, the romance, the ‘feel-goodness’ that supposedly redefined Hindi cinema. But I remember thinking even then: what’s everyone so excited about? Growing up on the cinema of Amitabh Bachchan – the restless, simmering energy of Deewaar, Trishul, Kaala Patthar as also the quiet anger of Alaap and Bemisaal – I found DDLJ a little too … soft. In that era of rebellion and wounded masculinity, Raj seemed to me the anti-angry young man, not in a revolutionary way, but in a timid, almost compliant one.

It’s not that I had anything against Shah Rukh Khan. In fact, I had taken to him early, precisely because of his unpredictability. There was a charge, a danger, in those first few years: Baazigar, Darr, Kabhi Haan Kabhi Na, even Anjaam. He was edgy, erratic, magnetic, characters with a volatility running through the charm. The characters felt human, fallible, alive. You didn’t know what he might do next. That, to me, was thrilling. And then came Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, a film so squeaky-clean, so one-dimensional, that it seemed to scrub all the grime and moral ambiguity out of his persona. It marked, for me, the end of my fandom. The dangerous boy had been domesticated. The rebel had been repackaged as the nation’s ideal son-in-law.

I could admire DDLJ as a cultural phenomenon, but I could never love it. And thirty years later, with the film still running at Maratha Mandir, I realize I stand among the minority that never quite bought into the magic.

The Return of the Dutiful Hero

It’s easy to forget how seismic DDLJ was in 1995. Hindi cinema was emerging from the hangover of the 1980s, a decade of formulaic action dramas, cheap thrills and forgettable music. Aditya Chopra’s debut came like a breath of Swiss air – clean, Western, glossy. But beneath the freshness lay a quiet conservatism.

Raj, the NRI boy who flirts, teases, drinks, yet refuses to ‘elope’ because he must win the father’s approval, was positioned as a new kind of hero. Western in manner, Indian at heart. For many, that balance was irresistible. For me, it felt regressive. Raj, the supposed modern lover, ultimately bows to the very patriarchy that limits Simran’s freedom.

In the universe of DDLJ, love must first bend before it can stand tall. Raj’s romance doesn’t liberate Simran. It merely negotiates her transfer from one patriarch’s authority (her father’s) to another’s (her lover’s). The father must ‘give her away’ in the end. Raj’s big heroic act is not rebellion but permission-seeking. For a generation that grew up on the smouldering defiance of Bachchan, this was a strange new submission: rebellion rebranded as obedience.

It was as if Hindi cinema had traded its clenched fist for folded hands.

Simran’s Cage, Decorated with Love

Thirty years later, Simran’s plight feels even more suffocating. Watching her today, one sees not a dreamy young woman in love but a girl perpetually seeking approval – from her father, from Raj, from the moral code of the family. She wants to see the world, but even her dreams must fit within boundaries drawn by men.

When DDLJ released, Simran’s ‘obedience’ was often framed as virtue. She was the ‘good Indian girl’ torn between duty and desire. Did no one realize that what was being romanticized as sacrifice was nothing but submission? I wonder if today’s audiences, especially young women, can see through the romantic glaze. Do they still find it endearing that Simran waits for Raj to ‘come take her away’? Or do they have the agency to ask: why can’t she just go?

In the three decades since, Hindi cinema’s women have fought, sometimes successfully, for more agency. Characters in films like Queen, Highway, or even Jab We Met choose their own journeys. Against that backdrop, Simran looks like a fossil of a time when women’s choices were mere extensions of male decisions.

The Cultural Soft Power of a Patriarchal Fantasy

There’s no denying that DDLJ reshaped the idea of love in Indian cinema. It brought the diaspora into the mainstream, made the NRI aspirational, and offered a comforting image of ‘Indianness’ that could survive globalization. Raj was the Indian boy who could dance in Europe but still touch elders’ feet.

That mix – Western sheen, Indian morality – became Bollywood’s export model for years. The film’s success created a template repeated endlessly in the late ’90s and early noughties. The new Bollywood dream was global but conservative. Jeans and jackets, yes, but still arranged marriages, sanskar, family approval.

In hindsight, DDLJ might have been less a love story and more a cultural reassurance. It told a society anxious about liberalization that tradition would survive the winds of change. Its message was soothing: fall in love if you must, but don’t forget to touch papa’s feet before you do.

And that’s exactly why it never resonated with me. Because the films I grew up on did the opposite. They questioned, they raged, they broke things. Sometimes literally. Vijay in Deewaar didn’t ask for permission; he walked out of home and built his own moral world. DDLJ asked us to return home, obediently, smiling, in time for the wedding.

The Raj Archetype, Revisited

If the angry young man was the cinematic product of political and social unrest, Raj was born from the new India of consumerism and middle-class comfort. He didn’t fight the system because the system now looked good with its mustard fields, imported beers, and affable fathers who eventually tear up and bless you.

But even within that comfort, there was a quiet control. Raj’s charm, and his eventual moral superiority, depended on being the ‘good guy’. He flirts but never crosses the line, he teases but never touches, he drinks but still respects elders. His virtue is not spontaneous; it’s performative. It’s as if the film spends three hours assuring us that Raj is safe, that this love story won’t disrupt social order.

For someone who had admired Shah Rukh’s earlier darkness – his willingness to play men who lost, who obsessed, who killed, who failed – this newfound moral correctness felt sanitized. The Shah Rukh of Darr or Baazigar (not that they were aspirational or worthy of emulation) didn’t seek approval; he demanded attention, he unsettled you. DDLJ domesticated that fire, turned the anarchic energy into a boy-next-door grin. It’s almost as though Bollywood itself decided that the dangerous lover was too risky. Better to turn him into a brand ambassador of virtue.

From Switzerland to Screens: The Legacy

For thirty years, DDLJ has been enshrined as Bollywood’s most beloved love story. Every few years, a new article celebrates its ‘timelessness’. Couples re-enact scenes, families revisit it as ritual. I wonder if the cracks I discerned even at the time are visible to the modern viewer. Or are we – like andhbhakts who insist on seeing the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as histories and not the mythologies they actually are – closed to the insidious messaging of the film?

Do younger viewers watch the film differently? Are they less enchanted by its romance and more aware of its control mechanisms? Does the train scene that once made hearts flutter now raise eyebrows? Do we question: Why should Simran’s freedom depend on whether Raj extends a hand? Why must her liberation look like rescue?

Even the idea of love that DDLJ sold – patient, parent-approved, socially acceptable – feels at odds with the messy, self-defined relationships of today. In a world of online dating, mental health awareness, and individual autonomy, DDLJ’s love looks less eternal, more curated.

The Myth of ‘Harmless Romance’

For decades, DDLJ was held up as proof that romance could be pure, non-violent, ‘family-friendly’. But purity itself is a coded word. What it meant was: love that doesn’t question tradition, love that knows its limits. Simran’s ‘yes’ at the end comes after every man around her – father, lover, friend – has spoken. Her consent is the last in the chain. That’s the unsettling truth behind DDLJ’s sugar-coated narrative. It tells women: it’s okay to desire, as long as you desire within the boundaries we set. That is largely true of Indian society even today, but DDLJ makes it acceptable, worthy of being emulated.

The film doesn’t just reflect patriarchy; it reaffirms it with smiles and violins. It turns oppression into romance, control into devotion. And we all applauded because it came wrapped in chiffon and nostalgia. That, to me, is its most cunning triumph: to make obedience look like love.

What the Modern Simran Knows

I hope today’s Simran doesn’t need to wait at a railway station. That she has her own ticket, her own journey. That she doesn’t need Raj to hold out a hand. Many young women I speak to find DDLJ difficult to connect with. It’s not that they reject romance – it’s that they reject dependency. Their love stories may still be chaotic, but they are theirs. They don’t want to be chosen; they want to choose. They defy sanskari diktats of right-wing loonies who want women to dress a certain way. And yet the ease and willingness with which they fall in line with the regressive aspects of festivals like karwa chauth tells another aspect of our society. Do modern Simrans realize that when they ‘give up on Raj’, they’re not giving up on love? They are giving up on the hierarchy that DDLJ romanticized with such fanfare?

What Remains

To deny DDLJ’s impact would be dishonest. It revived romance in Hindi cinema, redefined stardom, and gave the industry a visual grammar that endured for decades. It’s impossible to talk about Bollywood without acknowledging its shadow.

But as I revisit it now, thirty years later, I see it not as a milestone of progress but as a monument of transition, a bridge between the rebellious cinema of the ’70s and the sanitized family dramas of the late ’90s. It reassured a society in flux that change need not be threatening.

For many, that reassurance was comforting. For me, it felt suffocating. I longed for cinema that unsettled, not soothed. That questioned, not consoled. DDLJ wanted us to come home. The films that shaped me wanted us to walk away.

The Train Still Runs but I Never Bought a Ticket

Thirty years later, DDLJ still plays every day in Mumbai’s Maratha Mandir like a cultural relic in motion. Tourists visit it like a shrine; couples still take photos in front of the poster. But perhaps that’s where the film truly belongs now – in nostalgia, not in aspiration.

For me, the film remains a paradox. A dazzling, sentimental spectacle built around a hollow idea of love. A love that negotiates rather than liberates, that pleases fathers more than fulfils lovers.

And maybe that’s why I never boarded that train. Because somewhere, in another compartment of Hindi cinema, Deewaar’s Vijay was still telling Daavar, ‘Main aaj bhi phenke hue paise nahi uthata.’ That line – raw, defiant, angry – spoke to me more than all the violins in Switzerland.

Leave a comment