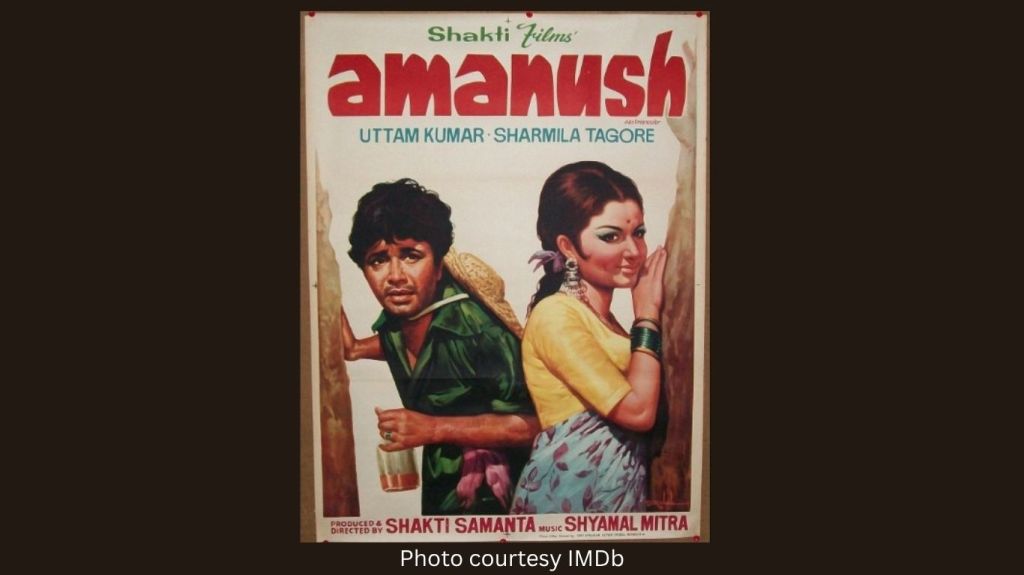

Much has been made of Uttam Kumar’s failure to break through in Hindi films. I look at what remains his only successful venture in Hindi as Amanush turns 50.

In 1975, Hindi cinema witnessed a curious phenomenon. A man who needed no introduction in Bengal, Mahanayak Uttam Kumar, suddenly lit up the Bombay box office with a film that was equal parts melodrama, romance and star charisma. For decades he had reigned unchallenged in Bengali cinema, but his forays into Hindi had floundered. Then came Amanush, directed by Shakti Samanta and released almost simultaneously in Bengali (October 1974) and Hindi (March 1975), to break the jinx. Fifty years later, it still remains his only box-office success in Hindi, a fascinating anomaly in Indian cinema.

It is one of those ironies of filmdom that an icon of his stature could come such a cropper in Hindi cinema. It is even stranger when you realise that so many of his Bengali film classics went on to be remade in Hindi with great success. These include Amar Prem (Nishipadma), Angoor (Bhranti Bilas), Lal Patthar (Lal Pathor), Bemisaal (Ami Shey o Sakha), Hum Dono (Uttarayan), Kala Pani (Sobar Opore), Chupke Chupke (Chhoddobeshi), Anurodh (Deya Neya) and Jeevan Mrityu (Jeebon Mrityu).

The Bilingual Experiment

By the mid-1970s, Shakti Samanta was one of Bombay’s most successful directors, having delivered blockbusters like Aradhana (1969), Kati Patang (1971), and Amar Prem (1972). But he also had deep roots in Bengal, and with Amanush he began a series of bilingual ventures. The film was shot in Bengali and Hindi with the same cast, adjusting only the language of the songs and dialogues.

This bilingual format gave Samanta two advantages. In Bengal, Uttam Kumar’s presence alone guaranteed audiences. In Bombay, where Uttam was an unknown quantity, Samanta cushioned him with familiar Hindi cinema tropes, familiar co-stars, and a musical score that could travel across regions.

The Sunderbans Setting

Amanush is set against the lush, swampy backdrop of the Sunderbans, with its endless rivers, mangroves, and boats cutting through mist. This setting gave the film a distinctive texture. The natural beauty and isolation of the Sunderbans became a metaphor for Madhusudan Roy Choudhury’s (Uttam Kumar) emotional desolation: marooned by betrayal, lost in the wilderness of alcohol and despair, yet ultimately redeemed.

For Hindi audiences, this was a refreshing change from the urban settings or hill-station romances that dominated the period. For Bengali viewers, the milieu was instantly recognisable, rooted in a landscape that was part of their cultural imagination.

Why Amanush Clicked in Hindi

For years, Uttam Kumar’s Hindi attempts had failed. Chhoti Si Mulaqat (1967), his own ambitious production with Vyjayanthimala, flopped disastrously. Films like Dooriyan or Ananda Ashram that came later never registered in Bombay. What made Amanush the exception?

One, Madhusudan Roy Choudhury is the archetypal wronged hero – betrayed by his scheming munim, falsely implicated, reduced to a drunkard, and resurrected by love and self-belief. This arc resonated with Hindi cinema’s tradition of the fallen but noble protagonist, from Devdas to the angry young men of the 1970s.

Two,Samanta knew exactly how to pitch Uttam to a Hindi audience. He avoided arthouse subtlety and leaned into melodrama, crafting big emotional set-pieces that allowed Uttam to perform for the gallery. The Hindi audience never saw the understated Uttam of Nayak or Harano Sur, but they got a man in ruins and in flames, which worked commercially. Surrounding Uttam with familiar Hindi stars helped. Sharmila Tagore, by then an established Bombay heroine, gave the film a romantic anchor. Utpal Dutt provided a prefect villainous foil. These actors made Uttam’s presence appear less alien.

Hindi films live and die by their music, and Amanush had a soundtrack that travelled. Shyamal Mitra composed, with lyrics in Hindi by Indeevar. The standout was ‘Dil aisa kisi ne mera toda’, sung by Kishore Kumar, which became a chartbuster. Kishore’s plaintive voice, combined with Uttam’s anguished screen presence, struck a chord. Suddenly, Uttam had an anthem in Hindi, something his earlier films lacked.

Not Among His Best but Massy

Interestingly, Amanush is rarely ranked among Uttam Kumar’s great works. For connoisseurs of Bengali cinema, his collaborations with Satyajit Ray (Nayak, Chiriyakhana), Tapan Sinha (Jhinder Bandi), or Ajoy Kar (Harano Sur, Saptapadi) showcase the breadth of his artistry. Compared to those, Amanush is simplistic, veering into melodramatic excess. But therein lay its success in Hindi: it was ‘massy’ in a way his more nuanced Bengali films were not.

Uttam’s performance in Amanush is pitched to the gallery. Eyes bloodshot with drink, voice slurred in despair, then rising to righteous indignation when the tide turns. For audiences used to the raw intensity of an Amitabh Bachchan or a Rajesh Khanna, this fit well into the mood of the mid-1970s. The ‘angry young man’ was making waves, but there was still a place for the tragic-romantic hero clawing his way back from ruin. It was the very excess that worked. Hindi cinema audiences in 1975 were still receptive to operatic emotions, and Uttam’s performance – drunken rages, slurred despair, noble defiance – fit right in. It was his most ‘massy’ performance, tailored to a pan-Indian sensibility, even if it sacrificed some of the finesse that defined his Bengali roles.

The contrast becomes clearer when we consider his other Hindi outings. Chhoti Si Mulaqat, produced by Uttam himself, was meant to launch him in Bombay. Despite Vyjayanthimala as co-star and Shankar-Jaikishan’s music, it collapsed at the box office. The story lacked punch for a Hindi audience, and Uttam’s Bengali cadences in Hindi dialogues jarred. The failure left him financially scarred. Dooriyan was a family drama with Sharmila Tagore, directed by Bhimsain, which tackled themes of marital discord. Though well-meaning, it was too understated for mainstream success. Ananda Ashram was another Shakti Samanta bilingual with Sharmila. But lightning didn’t strike twice. The narrative felt derivative, and Uttam lacked the fiery arc that had made Amanush work.

In short, Uttam’s Hindi films either leaned too heavily on subtle domestic drama (Dooriyan), or lacked high-voltage melodrama (Chhoti Si Mulaqat). Amanush hit the sweet spot: big emotions, sweeping music, and a redemption arc that resonated.

The Bengali-Hindi Divide

Even in success, Amanush highlighted the challenges of bridging two cinematic cultures. In Bengal, Uttam’s persona was deeply embedded in a cultural fabric that valued subtlety, charm, and a distinctly Bengali romanticism. In Bombay, stars were larger-than-life, their voices and mannerisms broadcast across a national audience.

Amanush is by no means anywhere near the best of Uttam Kumar as an actor – in fact, this is the closest to hamming I have seen from the star, though he conveys the anger and angst of the character rather well. In fact, the success of the film underscores the point I have often made about Hindi film stars having to operate at a decibel a notch or two above what was expected of their colleagues in the Bengali industry. And the discomfort shows even in Amanush.

However, the film clicked with the audience big-time and became the biggest hit of his career in both languages. It also spawned a Telugu version, Edureeta, starring N.T. Rama Rao, and one in Tamil, Thyagam, starring Sivaji Ganesan. But by this time Uttam Kumar was fifty and showing it, his girth not helping his cause in an industry that swore by hulks like Dharmendra and Vinod Khanna.

Uttam’s accented Hindi, his Bengali cadence, and his slightly aloof presence were often cited as barriers to his wider acceptance. Not to mention his two left feet, so obviously and jarringly visible with his attempt at a twist in Chhoti Si Mulaqat. In Amanush, these were mitigated by careful dubbing (or at least careful dialogue delivery), and by surrounding him with familiar Hindi elements. But the success was not repeatable. His follow-up bilinguals, like Ananda Ashram (1977), failed to replicate the magic, despite a classic music score composed by Shyamal Mitra with three Kishore Kumar gems in particular: ‘Raahi naye naye’, ‘Saara pyaar tumhara’ and ‘Tere liye maine sabko chhora’.

The Supporting Cast

For Bengali audiences, Uttam and Sharmila carried the weight of their shared screen history. Sharmila had first acted opposite Uttam in the Bengali film Shesh Anko and then Nayak. By 1975, she was an established Hindi star, balancing commercial hits with Satyajit Ray’s Aranyer Din Ratri and Gulzar’s Mausam.

In Amanush, she is the beloved whose rejection of the hero adds to the film’s dramatic component, symbolizing his total rejection by society. It provides the hero another impetus to pull himself out of the morass and prove himself. In Bombay, Sharmila’s presence gave Uttam’s unfamiliar persona legitimacy. She was the bridge between Calcutta’s matinee idol and Bombay’s audiences.

If Uttam was restrained in parts, Utpal Dutt went full throttle. As Mahim Ghoshal, the retainer who betrays Madhu, Dutt gives a performance steeped in sneer and theatrical malice. Dutt’s villainy is deliciously theatrical. He sneers, connives, and manipulates with a kind of larger-than-life gusto that Hindi audiences loved. Dutt filled the screen flamboyantly. Their confrontations, staged against the rivers and forests of the Sunderbans, are the film’s dramatic core, giving the film its dramatic weight.

‘Dil Aisa Kisi Ne Mera Toda’

If Amanush is remembered in Hindi cinema, it is above all for this song. Kishore Kumar’s voice brims with anguish, Indeevar’s lyrics capture heartbreak with simplicity, and Shyamal Mitra’s melody lingers with folk-like melancholy.

On screen, Uttam Kumar, glass in hand, broken yet dignified, became etched into Hindi popular memory. For many outside Bengal, this song is the only enduring image of Uttam Kumar. In the 1970s, when Kishore was the dominant playback voice, this song ensured Uttam’s entry into Hindi film culture was aurally secured.

The Cultural Context of 1975

The film also struck a chord with the mood of the nation. 1975 was the year of the Emergency, when distrust of authority and the sense of betrayal were widespread. A story of a man falsely implicated, betrayed by those close to him, and redeemed through resilience, resonated with audiences living in uncertain, repressive times.

At the same moment, Hindi cinema was undergoing transition. Rajesh Khanna’s star was dimming, Amitabh Bachchan’s angry young man was ascendant, but melodramatic romances still had room. Amanush fit into this in-between moment, before the full dominance of the action-oriented 1980s.

Fifty Years Later: The Legacy

Amanush is not counted among Uttam Kumar’s masterpieces. But it occupies a unique niche. It remains the only film in which Bengal’s Mahanayak truly crossed over into the Hindi mainstream. For Bombay audiences, it offered a glimpse of his magnetism; for Bengalis, it was proof that their idol could conquer nationally, even if just once.

The bilingual experiment itself became a hallmark of Shakti Samanta’s career, though none of his later attempts matched Amanush’s impact (barring the Amitabh Bachchan starrer Anusandhan, the monstrously successful Bengali version of Barsaat Ki Ek Raat which had a tepid response at the box office). It also consolidated Sharmila Tagore as a pan-Indian star, and gave Utpal Dutt the launch pad for a formidable career in Hindi cinema. Above all, it gave Indian cinema one of Kishore Kumar’s most haunting heartbreak songs, indelibly tied to Uttam Kumar’s face.

Amanush endures not because it is great cinema, but because it is singular. It is the only film that allowed Uttam Kumar to break into Hindi consciousness, however briefly. Its lush Sunderbans setting, its melodramatic story of betrayal and redemption, its fiery villain, and above all its music made it possible.

Half a century later, Amanush remains an anomaly – the only Hindi film success of Bengal’s greatest star. It is not the best measure of Uttam Kumar’s artistry, but it is an invaluable cultural text in understanding the porous boundaries between regional and national cinemas in India. Its success was built on a perfect storm: Shakti Samanta’s commercial instincts, Sharmila Tagore’s star power, Utpal Dutt’s villainy, Shyamal Mitra’s music, and a melodramatic story arc that fit neatly into the Hindi audience’s taste of the time.

For one brief moment, the Mahanayak reigned in Bombay too. And if today his Hindi career is remembered only for this film, it is perhaps enough – because in it, Uttam Kumar found his one true Hindi anthem, one that still echoes fifty years on. Uttam Kumar remains, for the Hindi-speaking world, the man who once sang – or rather, was sung for – in Kishore’s voice: ‘Dil aisa kisi ne mera toda’.

It was enough to write his name, however briefly, into the annals of Bombay cinema.

Leave a comment