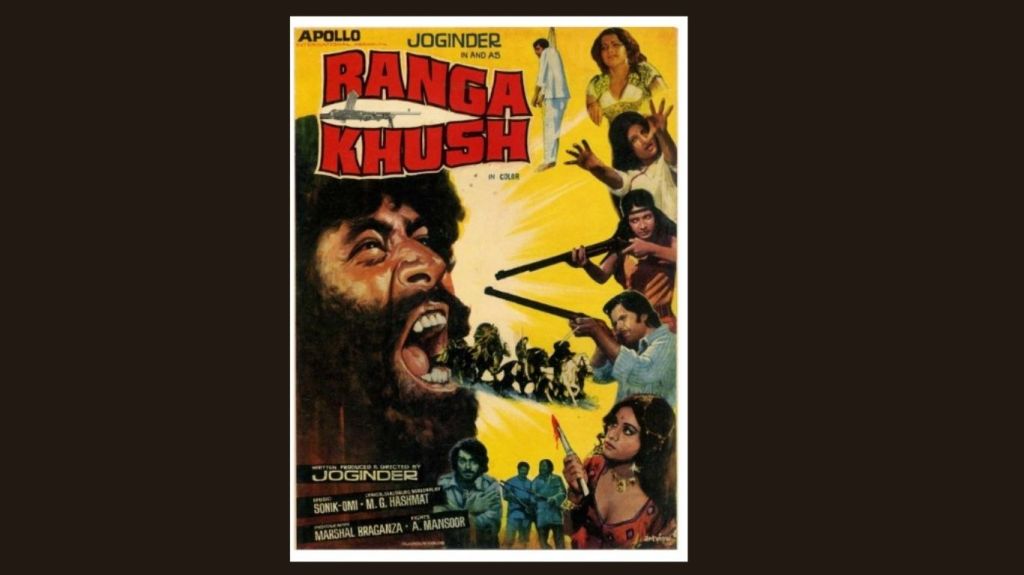

In the excitement of 50 years of 1975, the year that changed Hindi cinema with its justly celebrated films, we have overlooked one ‘cult’ film and its maker. I turn my gaze at the truly wonky Ranga Khush and Joginder, in the first of a series of films that have been guilty pleasures, films so bad they are unmissable…

In the vibrant, often chaotic landscape of 1970s Hindi cinema, dominated by megastars like Amitabh Bachchan and slick commercial formulas, a parallel current of cinema emerged – raw, regional and audacious. Among its most notorious icons was actor-producer-director Joginder. For many in that era, that mononymous name exemplified a world that probably could not be defined. Long before home video and digital distribution changed the game, Joginder carved out a career serving India’s small-town and regional theatres with a steady diet of scrappy genre films, many of which revelled in their chaotic energy and shoestring spectacle.

Few figures in India’s B-movie underground embody the spirit of cinematic anarchy quite like Joginder, a one-man film-making machine, often writing, directing, producing, and starring in his own ‘offbeat’ creations. In a way that mirrored the films and stature of Ed Wood, often described as among the ‘worst’ film directors ever. Like Wood, Joginder became known for churning out a string of low-budget, hastily made films that have since gained cult status for their campy aesthetic, crude visual effects, excessive use of unrelated stock footage, quirky dialogue and bizarre storylines. Despite these shortcomings, his knack for spectacle and self-promotion helped his work achieve a certain level of box-office traction.

His 1975 ‘cult classic’ Ranga Khush completes fifty years this year. Unfortunately, unlike Hollywood which celebrated Ed Wood with a wonderful biopic directed by Tim Burton, with Johnny Depp a pitch-perfect Wood, there is little interest in our country in a figure who carved his own unruly path through Indian cinema.

To understand Ranga Khush, however, one must also revisit Joginder’s earlier breakout film, Bindiya Aur Bandook (1972), which laid the foundation for his distinct style – a strange, compelling cocktail of action, melodrama, revenge and rural kitsch. Joginder’s first brush with popular success, Bindiya Aur Bandook was made on a small budget and starred newcomers, with Joginder himself as a key player in front of and behind the camera. The film’s rural setting, grounded in a dacoit-revenge theme, found unexpected resonance with audiences outside the urban metros, especially in north India. It told the story of a village girl who takes up arms against the men who brutalized her family and herself, a desi riff on the rape-revenge genre, long before it became a recognized category in Hindi cinema.

The film’s success lay in its pulp sensibility: rousing dialogue, outlandish violence, simplistic moral binaries, and unfiltered rural emotion. It was gritty but not polished, and that was precisely its appeal. Joginder’s rustic screen presence – bulky, moustached and volatile – struck a chord with audiences who were perhaps weary of the urban cool of Bombay stars. Bindiya Aur Bandook went on to become a sleeper hit, and its title itself became symbolic of a new kind of rural action cinema.

The film not only struck box-office gold but gave Indian audiences a catchphrase they couldn’t shake: ‘Ranga khush’ (echoes of ‘Mogambo khush hua’ years later in Mr India (1987). So iconic was that line that Joginder would go on to adopt it as a kind of cinematic alter ego, forever blurring the line between man and myth. As the phrase caught on, Joginder tapped into its potential with his next film, Ranga Khush, a delirious dacoit drama that lives on as both cult artefact and cautionary tale in the world of Indian exploitation cinema. Sensing the commercial potential, Joginder built an entire film around that persona in Ranga Khush, positioning himself as the titular antihero: a savage, unhinged bandit chief who looks more like a mythical beast than a man. Covered in matted hair and armed with a stare that could peel paint, his Ranga is part outlaw, part monster and wholly ridiculous in a way only Joginder could pull off.

But this isn’t just another dacoit revenge saga. Ranga Khush takes bizarre detours into supernatural territory, culminating in a climax so over-the-top it borders on religious fever dream. Facing off against an alliance of mythological and religious icons – Krishna with a laser, Jesus Christ, Mohammed, and even Hanuman – Ranga’s eventual downfall feels less like a moral reckoning than a cosmic intervention.

The film unfolds in a cave lair straight out of a fevered sketchbook, where Ranga rules over a kingdom of kidnapped children and unwilling wives. Chief among the latter is Devi (played by Nazima), a village girl forced into marriage and motherhood by the deranged bandit. Her brother Karma (Vikram) sets out to rescue her, which would make him the conventional hero, if Ranga Khush were anything close to conventional. Instead, the film fixates on Joginder’s magnetic weirdness, to the point where all narrative logic gets swallowed up by his performance.

And what a performance it is. Joginder doesn’t so much act as assault the screen: screeching, chirping, twitching, and rolling his eyes like a cartoon possessed. He punctuates his dialogue with high-pitched yelps and bursts of nonsense. I watched the film in a poor YouTube print and found myself at odds trying to understand what the actor was saying. I wasn’t sure if this was because of the print or because the actor’s maniacal performance truly defies understanding.

That it could have been the latter is in the realms of possibility as Todd writes in what is probably the finest tribute to the film (https://diedangerdiediekill.blogspot.com/2009/09/ranga-khush-india-1975.html): ‘In grand low-budget movie tradition, Ranga Khush depends more upon talk than action to advance its story. As such, without subtitles, it provides little to sustain interest among non-Hindi speakers, save, perhaps, for the sheer hypnotic force of Joginder’s bizarre performance. In his role as Ranga, the actor punctuates his dialog with an assortment of shrill chirping sounds and gibbering, high-pitched shrieks, coming across like some kind of helium-gorged Tourettes sufferer, while serving up the visual aspect of his portrayal in the form of near-constant eye rolling and gnashing of teeth … I’m confident that proper subtitling would reveal a whole treasure trove of quotable lines to us ferangi. Until then, the only way I can pay tribute to its late, great star is by gibbering incoherently like a rabid spider monkey with half of its head caved in.’ Despite being desi, I could have done with some subtitling to make sense of what was unfolding on-screen!

In the shadows of Ranga’s madness lurks Ginnibai (Chandrima Bhaduri), a black-clad sorceress who controls Ranga with an iron grip. It’s implied that Ranga was abducted as a child and raised to inherit the role of his bandit predecessor, possibly Ginnibai’s late husband. Now caught in her web of manipulation, Ranga is less villainous overlord than broken puppet, a screeching, sobbing man-child in constant emotional freefall.

Despite the insanity, or perhaps because of it, Ranga Khush was a hit in its day, further cementing Joginder’s cult status. Over time, the film’s unfiltered strangeness and bargain-bin bravado have earned it a place in the hearts of B-movie lovers, particularly those drawn to cinema that dares to be profoundly, unapologetically weird. In many ways it was the progenitor of the Gunda-s and Raavan-s that defined Mithun Chakraborty’s latter-day career. It’s hard to say if Ranga Khush was ever meant to be taken seriously. But there’s no denying its status as a singular artefact of Indian exploitation cinema, a film that wears its absurdity like a badge of honour and finds accidental profundity in its own chaos. The film reportedly found its way in discussions in the Rajya Sabha which debated its ‘rape sequences and insults to religious deities of all faiths’.

The film made him a household name in many parts of India. Ranga was no ordinary villain. With his trademark growl, outlandish costume (often just a tattered vest and dhoti), and demonic laughter, he became a character both terrifying and oddly charismatic. The line ‘Ranga khush!’ delivered with snarling gusto, became part of the film’s mythos. In Ranga, Joginder created a villain so distinctive and hyperbolic that he almost became the protagonist, a trend that would be echoed later in Hindi cinema with characters like Gabbar Singh in Sholay (also released in 1975).

But unlike Sholay, Ranga Khush did not benefit from industry polish or critical appreciation. What it had was raw appeal, a word-of-mouth-driven popularity, and deep rural penetration. Its distribution followed unconventional routes: low-cost prints sent to single screens and touring cinema tents across north and central India. The film was a box-office success in these circuits, despite being largely ignored by the mainstream press.

Style, Sensation and Subversion

Joginder’s film-making style was unrefined but instinctive. He knew his audience and gave them what they craved: larger-than-life villains, righteous revenge, rural justice and high melodrama. His films weren’t concerned with cinematic grammar but with immediacy and impact. In Ranga Khush, scenes were staged like street theatre: over-the-top yet intensely engaging, often punctuated with vulgar humour, graphic violence, and long-winded monologues that bordered on the operatic.

Critics often dismissed Joginder’s work as ‘C-grade’ or ‘sleazy’, but such labels miss the point. His cinema was not made for elite critics or urban cinephiles. It was for the masses who found little identification with upper-class, English-speaking protagonists. In Joginder’s world, the oppressed got their revenge, and evil was shouted down – not through diplomacy, but with bullets and blood-curdling catchphrases.

This subversive energy is what makes Ranga Khush worth revisiting. The film flipped conventional hierarchies: the villain dominated the narrative; the moral order was blurred; and the rural gaze was not mediated through city sophistication. It was folk cinema wrapped in film reel.

Joginder the Persona

Beyond the films, Joginder cultivated a persona that further cemented his cult status. He would often show up in public events in character, sometimes dressed as Ranga himself. He claimed to have written scripts that were stolen by mainstream film-makers (famously, he filed a lawsuit alleging that Sholay borrowed from his ideas). While the case did not go anywhere, it fed into the Joginder mythos: the outsider who took on the establishment.

Years later his unbridled cheek came to the fore when he not only dared to set up his Bindiya aur Bandook-2 in a box-office clash with J.P. Dutta’s LOC Kargil but even emerged the winner at the turnstiles. While Bindiya aur Bandook-2 went houseful in B and C centres, LOC Kargil flopped. There were also reports that he made Pyasa Shaitan by re-editing an already existing Kamal Haasan film and inserting himself into it.

His cameos in 1980s potboilers like Anil Sharma’s Hukumat and Elaan-e-Jung and Raj N. Sippy’s Loha proved his popularity among audiences. As an inveterate 1980s film junkie who watched the worst the decade had to offer in the theatres, I was personally witness to the crazy whistling, the catcalls and the general cacophony that accompanied his every appearance on-screen. And his 90-second bhangra with Amitabh Bachchan in Mard, gyrating to the words ‘Jaako rakhe Saiyan, maar sake na koi’, has gone down as one of the cult moments of Hindi cinema of the decade.

In a way, Joginder was the precursor to the ‘indie maverick’ of today’s cinema ecosystem, but working in a vastly different idiom. His do-it-yourself model, complete with local marketing, grassroots distribution and self-promotion, was ahead of its time. He owned his niche, even if the mainstream never truly accepted him.

The Cult of Ranga Khush and Its Legacy

As the decades passed, Ranga Khush acquired cult status. It was rediscovered in the VHS era, featured in compilations of bizarre Bollywood, and eventually gained attention from cinephiles who viewed it as outsider art. Joginder became a figure of ironic celebration in the internet age, where fans of B-movies and pulp cinema hailed him as a legend of the underground.

What’s striking is how Ranga Khush has aged, not like fine wine, but like a stubborn local brew: unrefined, pungent, yet deeply authentic. It remains a reminder of the diversity within Indian cinema. A space that includes not just the celebrated auteurs or suave stars, but also rogue film-makers like Joginder who made films with sheer audacity and no concern for convention.

Fifty years after its release, Ranga Khush stands as a testament to a forgotten, feral stream of Hindi cinema that existed outside the purview of awards and multiplexes. Joginder carved out a legacy not through cinematic finesse but through instinct, bravado and an unshakable belief in the power of spectacle. His films were unruly, noisy and often absurd, but they were never boring.

Joginder Shelly passed away in 2009 at the age of sixty-five, but his legacy lives on, especially whenever someone imitates his deranged Ranga shriek or mutters ‘Ranga khush’ under their breath with a crooked grin. Whatever else he was, Joginder made sure we’d never forget him.

In an age where independent cinema often equates to minimalist storytelling and urban realism, Joginder’s body of work reminds us of another kind of indie: maximalist, popular, raw and defiantly regional. As Ranga Khush turns fifty, perhaps it’s time to revisit and recognize the many shades of Indian cinema, especially the ones that came screaming out of the shadows.

Leave a comment